The Old Schwamb Mill’s glue room is one of its timeless interior spaces. Located at the northwest corner of the main building’s second floor, its windows overlook Mill Brook and Mill Lane. Indeed, the glue room is a time capsule illustrating a key step in the frame-making process: the gluing of the frame quadrants. Here, the visitor will see the flat radiator where the quadrants and particularly their jointed ends were heated up to allow ample time to assemble the entire frame before the glue cooled and set. Suspended just above the flat radiator is a bucket where the hide glue was heated in a double boiler, triggering the transformation from hard, sand-like crystals soaking in water to a gooey, liquefied substance which was then brushed on to the joints at the ends of the quadrants.

Dominating the center of the glue room is a large, glue encrusted table where the frames are strapped into steel band clamps connected by gears with iron wheels resembling steering wheels. The wheels wind the clamps tightly around the frames to insure that the glue sets evenly. Today the frames remain tightly strapped into the clamps for eight-to-ten hours at which point the clamps are loosened and the frames taken downstairs to be worked on at the face-plate lathes. The hide glue used in the Schwambs’ time set more quickly as it cooled. Hide glue created a bond stronger than the wood itself as long as the wood was clean and the parts fit snugly (thanks to help from the band clamps).

What Is Animal Hide Glue?

The Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online (CAMEO) defines animal hide glue as “a strong, liquid adhesive consisting primarily of gelatin and other protein residues of collagen, keratin, or elastin.” Collagen forms a molecular bond with the glued object. Hide glue has been made for thousands of years from skins of animals including goats, sheep, goats, cattle, horses, etc. Other types of animal glue are characterized by collagen found in animal bones, tendons and other tissue. Organic glue is also derived from fish and rabbits.

According to Bob Flexner in Popular Woodworking Magazine, October 12, 2009, “Animal hide glue is made by decomposing the protein, or collagen, from animal hides. Almost any hide can be used, including horsehides (“take the horse to the glue factory”). In modern times, however, cowhides are universally used.” Prior to the early twentieth century, horses were much more readily available because of their widespread use for commerce and transportation. Flexner notes that “[t]he hides are washed and soaked in lime for up to a month to break down the collagen. After being neutralized with an acid, the hides are heated in water to extract the glue. The glue is then dried and ground into Grape-Nuts-sized granules, which is the form in which it is usually sold.”

Brief History of Animal Glue

Long before animal hide glue, vegetable-based glues were employed to act as an adhesive substance. A wide variety of vegetable glues are derived from starches, gums, cellulose, bitumen and natural rubber, and they all have specific applications. Reportedly, Neanderthals used a plant-based adhesive 17,000 years ago to protect their paintings from moisture in France’s Lascaux caves.

Animal hide glue rose to the fore around 6,000 years in South Africa and was used to repair ceramics. Perhaps not surprisingly, Egypt was the birthplace of the use of common animal glue. Animal glue was first introduced in Ancient Egypt some four thousand year ago, which is earliest known confirmation of use of glues that were made by prolonged boiling of animal hides, hooves and connective tissue. The Egyptians used animal glues to adhere to furniture, ivory, and papyrus. Indeed, animal hide glue has been found on the furniture and caskets of Egyptian pharaohs.

According to the L.D. Davis’s Glues and Gelatins blog, the first known written procedures for making glue date to as early as 2,000 B.C. The Mongols — including Genghis Khan — and the Native Americans used glues to make everything from bows to canoes.

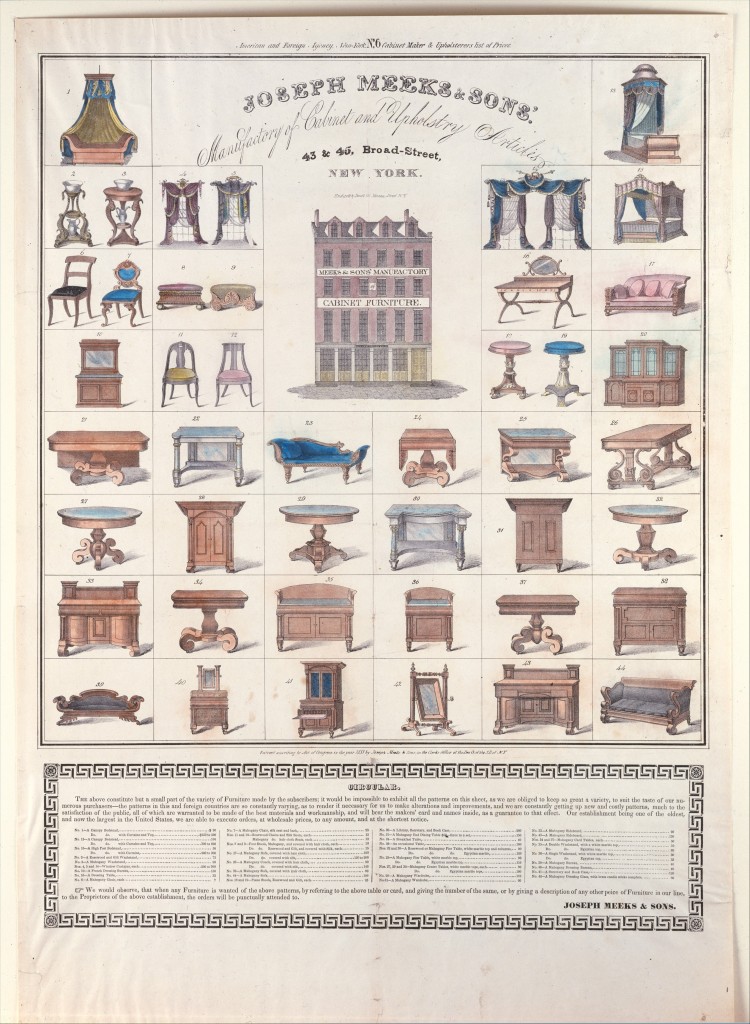

Fast forwarding from Ancient Egypt to Europe, during the 1500s and 1600s hide glue was used in the making of fine furniture by highly skilled artisans (as seen in France as the furniture-making industry ramped up during Louis XIV’s regime and continuing apace through the eighteenth-century reigns of the Louis XV and XVI). By 1700, the first glue factory was established in the Netherlands with similar enterprises springing up in England and the German states. By the mid-1700s, animal glue was used in the creation of violins and other types of musical instruments. During the Colonial period, American craftsmen making fine furniture in port cities along the eastern seaboard used hide glue with this practice continuing through the Federal period as seen in the work of Duncan Phyfe and Charles-Honoré Lannuier. Beginning in the mid-1830s, mass produced mahogany veneer Late Empire furniture was made with steam-powered tools and hide glue as seen in the work of Joseph Meeks of New York City and hundreds of other American companies.

The Schwamb factory of Arlington, like many wood shops in the United States during the 1800s, used hide glue in the manufacture of their picture frames. Historically, animal hide glue was the only game in town until the mid-1900s with the introduction of modern synthetic glue. Animal hide glue was used by the Schwambs in the production of their picture frames from the very beginning of their enterprise in 1840s until they closed the business in the summer of 1969. Even as modern, synthetic glue increasingly dominated the adhesives market after World War II, the Schwambs stuck by hide glue because of its many positive qualities, starting with the fact that it set quickly – a crucial advantage for a company that the Arlington Advocate reported in 1872 was making thousands of picture frames a week (Arlington Advocate, 8/10/1872, p. 2, col. 1).

Unlike other adhesives, hot animal hide glue bonds in two steps. An initial tacking occurs when the glue cools from its application temperature of 140-150° Fahrenheit to about 95°F. The bond becomes complete when the water evaporates out of the glue.

That the Schwambs did not adopt synthetic glue is not surprising. For them, hide glue worked. Furthermore, hide glue is easily reversible and long-lasting. Mistakes could be easily corrected and consequently customers would not be complaining about any lack of durability.

The Clinton W. Schwamb Company’s ledgers document the factory’s use of glue in the twentieth century. When business was good, in the mid-1920s for example, it appears that the factory used 400-500 pounds of hide glue in a year. A typical order would be for 200-300 pounds. They ordered from four companies primarily, including:

J.O. Whitten Co., 68 Western Ave. Boston, Mass. The Whitten Company was located on the south east side of Western Avenue between Soldiers Field Road and North Harvard Street. The company occupied the buildings of the Flint Varnish Company as seen on the 1897 George Stadley Boston Atlas. Since glue is a by-product of animal rendering, it is not surprising that the Whitten Company was located near the Brighton Abattoir, located further to the west off of Western Avenue. In 1876, Brighton’s 66 slaughter houses were consolidated into one facility known as the Brighton Abattoir. Whitten came to operate a factory at 120 Cross St., Winchester, Mass., in the twentieth century.

Russia Cement Company, 147 Essex Ave, Gloucester, Mass. This company was also the maker of LePage’s glue, including “Mucilage” and other household adhesives.

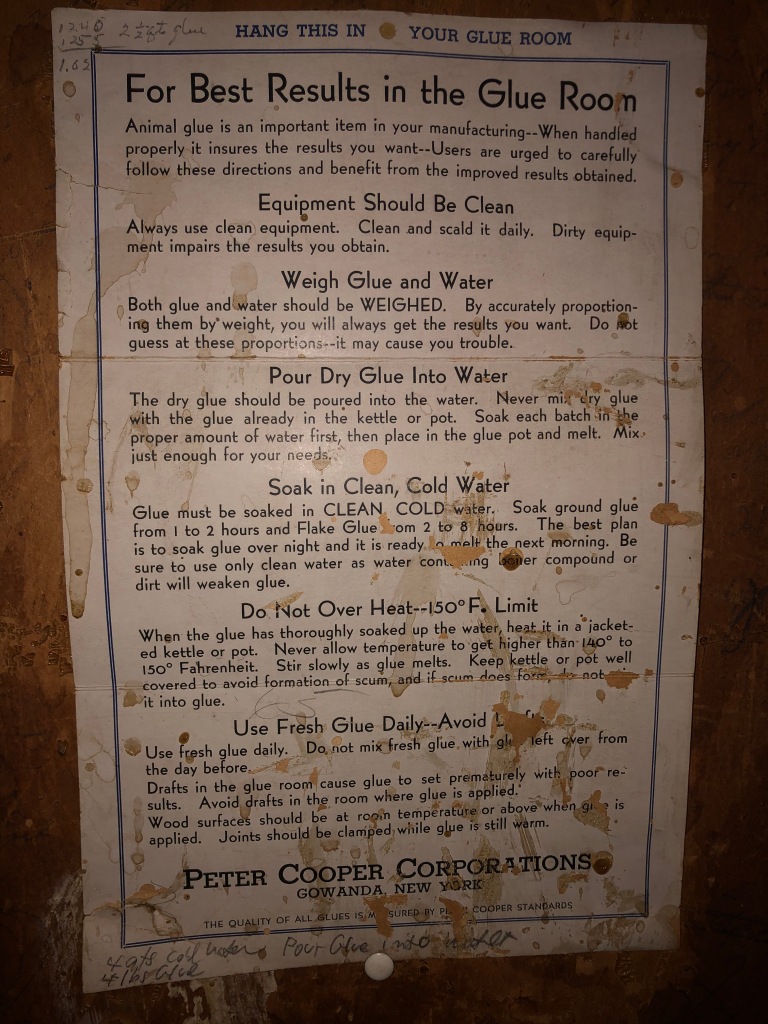

Peter Cooper’s Glue Factory, Gowanda, NY. Gowanda, near Buffalo, was the second home for this glue manufactory. The first was Brooklyn where the firm was founded in the nineteenth century by inventor and industrialist Peter Cooper. In addition to Cooper’s many industrial pursuits, he established The Cooper Union in New York City (also known as The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art which is a private college in Manhattan’s East Village).

Nicholson & Company, 161 First St., Cambridge, Mass. This company appears to have started production at this Cambridge location some time in the 1940s. It was a supplier of glue to the Schwamb mill in the late 1950s and 1960s.

The Schwambs may have also gotten glue from the American Glue Company, although most of their orders from that vendor were for garnet sandpaper and sanding belts.

Twentieth Century Rise in the Use of Modern Glue

In the 1930s, advances in the chemical and plastics industries led to development of a wide range of materials called adhesives and plastic or synthetic resin glues. World War II led to a further flowering of this industry when innovations in synthetic glue for the exclusive use of the military became commercially available during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

At the risk of sounding like a commercial endorsement, Titebond has been the glue of choice at the Old Schwamb Mill since the early 1970s. Most woodworkers encountering the glue room on a tour of the Mill concur that Titebond is their preferred glue because it requires no mixing, heating or stirring. Furthermore Titebond is exceptionally strong. It can be sanded and is unaffected by finishes. Bob Flexner in “Animal Hide Glue” (Popular Woodworking Magazine) notes that “Titebond is the same as hot hide glue, but with gel depressants added to keep it liquid at room temperature and preservatives added to retard deterioration for about a year.” Manufactured by Franklin International, Titebond is available in most hardware stores.

That Titebond rather than the more authentic animal hide glue is used at the Old Schwamb Mill museum has to do with the realities of current production. The Schwambs’ output of glued frames, even in its last years, might call for repeated use of the twelve gluing stations in the glue room. Fast setting glue was an advantage. Since 1970, the museum’s much smaller frame output (around 30-40 frames per year) makes the use of modern carpenter’s glue the sensible choice, avoiding the waste and short pot life of the hide glue and its unpleasant aroma.

Animal Hide Glue: Continued Viability in Niche Restoration Projects

Since the mid-1900s, animal hide glue’s use has been largely overtaken by synthetic adhesives. Nevertheless, it still holds a significant role in the repair and restoration of antique and reproduction furniture. In addition, glue derived from animal skins is still used in the restoration, production and repair of musical instruments. The use of hide glue in musical instrument-making may be traced back to the mid-1700s when animal glue was used in the creation of violins and other types of musical instruments. Hide glue’s desirability for this type of endeavor is inextricably bound to its characteristic quick setting which makes it ideal for the application of wooden veneers. Furniture restorers appreciate the fact that joints can be loosened by heating or steaming the old hide glue. In other words, the use of animal hide glue lives on in specialized restoration projects.

The use of animal hide glue in nineteenth and mid-twentieth century wood shops is illustrated during the course of a tour of Arlington’s Old Schwamb Mill.

Edward W. Gordon, Schwamb Mill Preservation Trust, Inc.

This period of reduced visitation due to the COVID-19 is a challenge for non-profits like the Old Schwamb Mill. Your contribution in support of the Mill, however modest, is much appreciated at this time. We look forward to reopening soon!

Bibliography

__________. “Clues On Glues.” Old House Journal, December 9, 2009. https://www.oldhouseonline.com/repairs-and-how-to/clues-on-glues

__________. “Facts About Hot Hide Glue.” http://www.player-care.com/hideglue.html

Ben. “Pere Cooper and His Glue. Brooklyn Public Library blog. August 5, 2011. https://www.bklynlibrary.org/blog/2011/08/05/peter-cooper-and-his-glue

Buck, Susan L. A Study of the Properties of Commercial Liquid Hide Glue and Traditional Hot Hide Glue in Response to Changes in Relative Humidity and Temperature. The University of Delaware, Winterthur Program in Art Conservation. http://www.wag-aic.org/1990/WAG_90_buck.pdf

Flexner, Robert. “Flexner on Fixing: Animal Hide Glue.” Popular Woodworking Magazine, August 2007, issue #163. https://www.popularwoodworking.com/aug07/flexner-on-fixing-animal-hide-glue/

Flexner, Robert. Animal Hide Glue, “Popular Woodworking Magazine”, October 11, 2009. https://www.popularwoodworking.com/finishing/animal_hide_glue/

Kirby, Ian. “When Hide Glue Ruled the Workshop.” Woodworker’s Journal, December 2007. http://gpaelgin.org/wp-content/uploads/hide-glue-workshop.pdf

Knight, Ellen. “From Eagle Tannery to Winchester Community Park.” https://www.winchester.us/DocumentCenter/View/3256/Eagle-Tannery

Brilliant material culture study!

Do you forward to anyone like the Deerfield folks, or the heir group from Peter Benes’ Durham, NH conferences?

This would be a great presentation and/or article.

DLa Rue

Donna La Rue, Independent Scholar, writing on “Dance and Sens Cathedral, Did They or Didn’t They?” and “The Place of the Arts in the Life of Faith” / http://independent.academia.edu/DonnaLaRue

a.k.a Mistress Elizabeth de la Rue ocbground.wordpress.com (@dwyndlelee)

82 Cleveland St Arlington MA 02474 Skype: ihsdlrue Email: ihsdlrue @ gmail.com

*pax in terra choragibus ballo non bello parare *

On Tue, Oct 20, 2020 at 6:59 PM Old Schwamb Mill wrote:

> dermotw posted: ” Thirteenth in an occasional series of Schwamb Shares The > Old Schwamb Mill’s glue room is one of its timeless interior spaces. > Located at the northwest corner of the main building’s second floor, its > windows overlook Mill Brook and Mill Lane. Indeed, t” >

LikeLike

Thank you Ed. Fascinating history! The glue room has always been one of my favorite places in the mill.

LikeLike

Ed, thanks for the great article. It brought back one of my earliest memories. As a youngster I read in the local newspaper that “the last milk wagon horse was being sent to the glue factory”. I had no idea what that meant. I fought back tears as my father explained to me that the horse was going to be made into glue.

LikeLike

Terrific informative article! Fragment here from my favorite sentence: “…the Schwambs stuck by hide glue.”

LikeLike