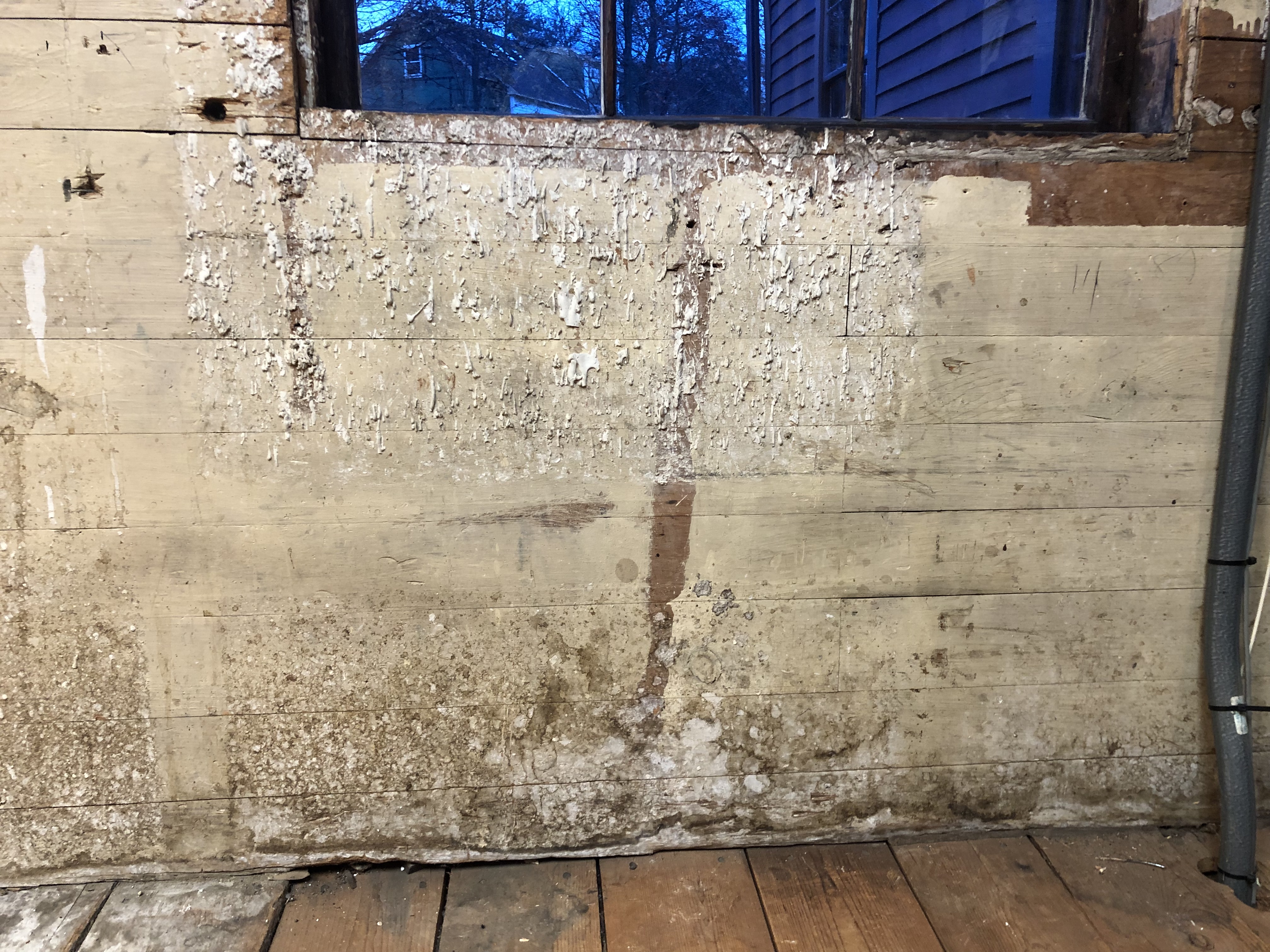

The walls of the Old Schwamb Mill are covered with pencil notes, painted memoranda (“First Snow”), newspaper clippings, and traces of the many finishes applied to frames and mouldings over the years. Of these finishes, gesso (or “whiting” as the Schwambs sometimes called it) is unmistakable. Here are some examples:

(l-r) Hand prints above gesso splatter in the second floor southwest wall.

(l-r) Graffiti was a by-product of the gessoing process. One joist near the Mill’s second floor west wall reads, “sic transit gloria mundi” a Latin phrase meaning “thus passes the glory of the world.” On another joist appears the name Henry Clay, the American Whig politician who died in 1852. Both instances have the ring of school-boy lessons. Louis Schwamb’s initials and those of other workers are found nearby.

Gesso was made by combining animal glue (traditionally rabbit skin glue) with powdered whiting. Gesso finishes were applied to mouldings and frames to give them a smooth, adhesive surface before gold leafing. Most gold leafing was done by the shops and galleries that purchased product from the Schwambs, but through the nineteenth century until the early 1920s, the Schwambs applied gesso to mouldings and frames, also selling raw wood frames.

Finishing frames in one fashion or another was a regular service offered by the Charles Schwamb and Son Company from its early days. The Arlington Advocate (and its sister publication, the Lexington Minute-Man) noted in 1875 that the oval frames were “carried to the finishing room where they are polished, varnished, or otherwise finished, as desired.”

On a visit to the Mill in 1881, the Advocate/Minute-Man described finishing in greater detail: “The floor above [i.e., the second floor] is devoted to the preparing, or “’whitening,’ white pine mouldings for gilding, the process being effected by a compact little machine which spreads the mixture over the wood with a perfect uniformity not otherwise attainable, and with great rapidity.” The article notes that the second floor space was nearly all taken up by finished mouldings drying on racks. The third floor is described as being used to finish “black walnut, ash, chestnut, oak, and some other painted or stained woods. Here the strips are rubbed, shelaced, [sic] polished, etc., as many times as are required to attain the proper finish…”

By 1897, the Schwambs were advertising locally that “Wall Papers may be matched on suitably tinted mouldings by furnishing samples of paper, on short notice.”

The Mill has a collection of gessoed and unfinished moulding samples dating as early as 1901, presumably created on site, for Boston area frame shops such as Doll & Richards, Foster Brothers, and J. F. Cabot. Some pictures of mouldings from 1910-11 show the smoothness of the work.

If a machine once applied gesso to the mouldings, we do not have a record of it. More likely, the gesso was drawn over the moulding profiles using a piece of metal with a cut out matching the moulding profile.

A machine once used to apply gesso to the oval frames does exist at the Mill. It was found in the attic by Patricia Fitzmaurice, founding trustee of the museum, and photographed in the 1970s as part of the HAER report on the Old Schwamb Mill.

Gesso wheel, photographed in the Mill’s attic in the 1970s as part of the Historic American Engineering Record, available online from the Library of Congress

Patricia Fitzmaurice recalled Elmer Schwamb referring to this as the “gesso wheel.” From the gesso splatter on many walls of the second floor, she surmised that gessoing had once been a part of the Schwamb Mill’s production. When Patricia interviewed Peter Jerardi, who worked at the Mill in his high school years from 1920 to 1922, he did not recall the machine shown above ever in use – though he did remember Louis Schwamb doing some gessoing of frames on a different, smaller machine.

We recently compared measurements of the gesso wheel’s base with the “shadow” cast by splattered gesso in one part of the second floor we now use as the Mill’s frame gallery. The measurements and the gesso wheel’s construction matched perfectly, so we temporarily move the wheel into position.

s

The shadow left by the splatter from the wheel shows the position of the legs and cross pieces against the wall.

We believe this is where the wheel stood and was used from approximately 1901 to sometime in the 1920s.

Other evidence in this room suggests that a counter was built to the left of the wheel as far as the wall above the old stair way. Running water was available a few feet to the right of the wheel. Two remarks appear on the wall above the work station:

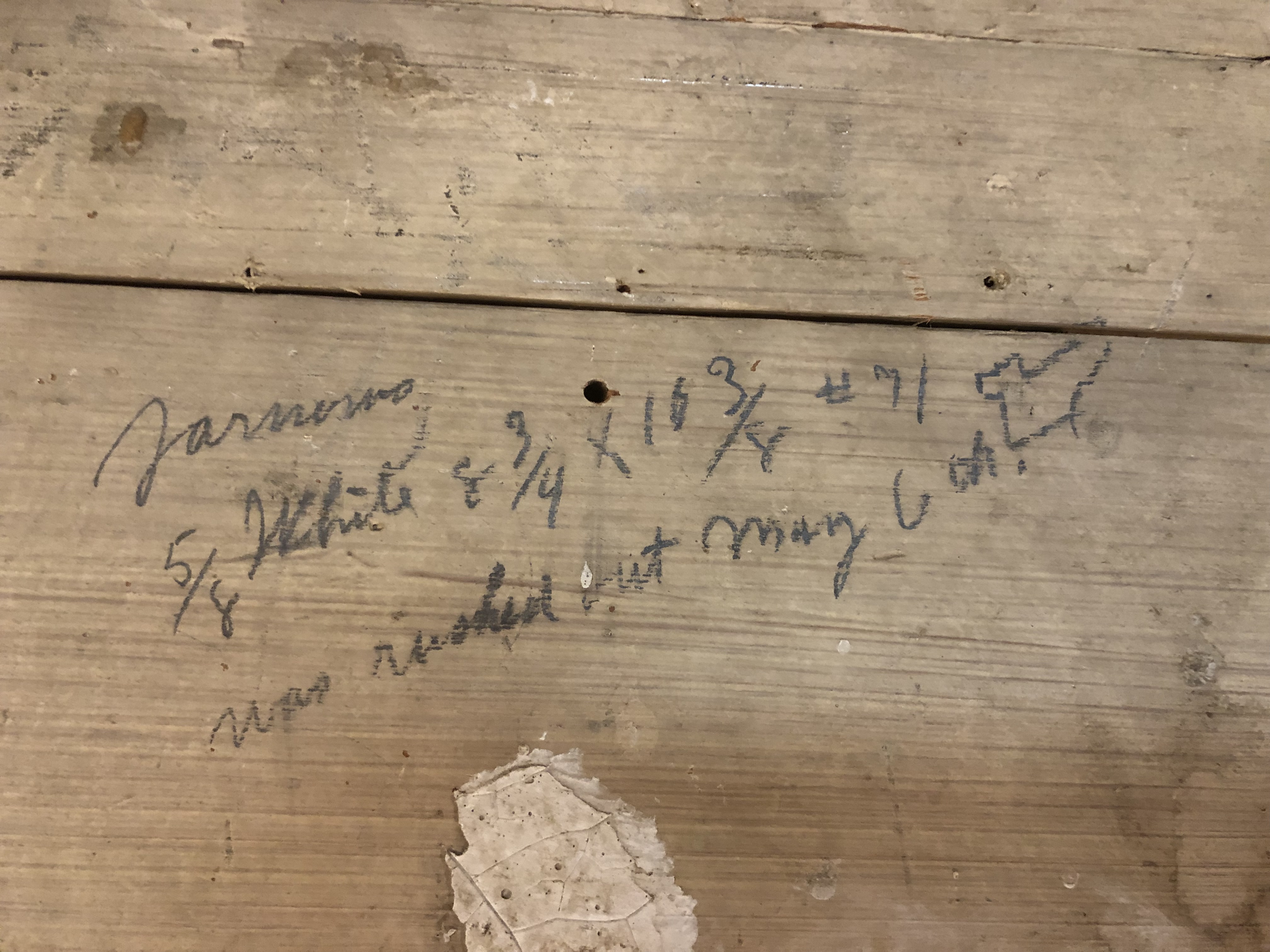

Jarnow 5/8 White 8 3/4 x 10 3/8 #72 was rushed out May 6

April 2 to 30, 1917 132 wt. frames

No sooner did we move the gesso wheel into position than we realized photographic evidence of the wheel in 1905 already existed. The evidence is in a picture we have viewed a hundred times — that of Louis and Clinton Schwamb holding a large frame in front of a worker (their father Carl William?) in the courtyard directly below the window. The gesso wheel is distinctly visible in both the 1905 image and one taken in November 2023.

Images of front of Old Schwamb Mill taken November 2023

Image of the front of the Schwamb Mill taken in 1905. The wheel appears to have two layers in this older image.

Just how this wheel worked in practice is still to be determined. It has an elliptical faceplate mechanism like the vertical faceplates used to turn the oval frames on the downstairs lathes. Our best guess at present is that either manually or through some power delivered to the pulleys on the underside of the device, the ovals were turned while a molding outline applied the gesso to the frame.

Some approximate recreations appear below.

Viewed from the top, the frame sits on the elliptical faceplate, allowing one side to remain in position relative to a hand-held tool that would apply the gesso evenly as the frame is turned on the wheel. Note that the shape of this profile used for this demonstration is not actually the same as the frame shown here.

From the order books available from November 1904, it appears that the Schwambs stopped doing gessoed frames by the early 1920s. In the grandchildren Clinton and Louis’s first year of business after taking over from their father, they produced 3306 gessoed frames, 56% of their total frame output. Ten years later, in 1915, their frame production had tripled, but they produced only 574 gessoed frames, a mere 3.4% of the total, with unfinished birch, bass, and oak making up the balance. By the mid-1920s, gessoed frames no longer appear.

It remained for Clinton’s son Elmer to rediscover the market for finished ovals. His side business The Elwane Company, bought unfinished ovals from the Clinton W. Schwamb Company, stained and lacquered them on the third floor, and sold them by the thousands across the United States, using sales agents to place the frames in over 700 stores. Thus the business came full circle from the finished oval frames Charles sold in Boston in the 1860s.

Dermot Whittaker, Schwamb Mill Preservation Trust, Inc.

In the Holiday season, Giving Tuesday is a reminder to all that non-profits depend on the generosity of donors. The Old Schwamb Mill is no exception. Please consider making a donation to the Mill securely online here.

Great research!

I have always felt that hand-holding the gesso scrapers wouldn’t work very well. I suspect they were held in place by a fixture.

LikeLike