In 1924, the Schwambs faced a problem. Their business had rebounded under the management of Clinton and Louis Schwamb, but they needed more power to increase production. Having ceased use of the Mill’s water turbine ten or more years earlier, they had two choices: increase pressures on the boiler that drove their steam engine or install electric motors to power the machinery.

The minutes of the Clinton W. Schwamb Company’s annual meeting describe the solution reached:

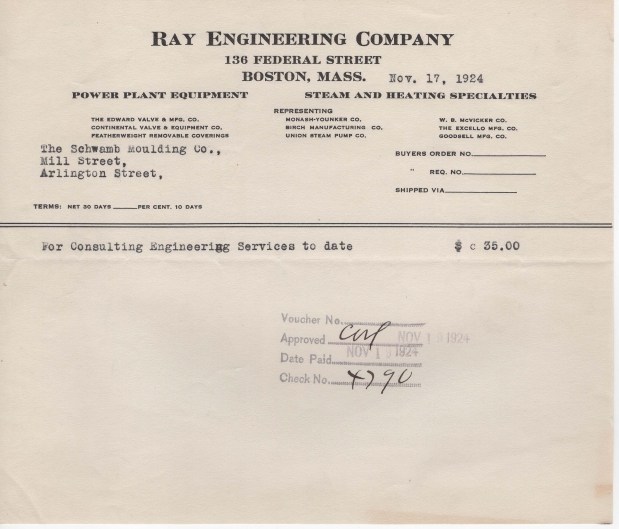

“During past year investigation was made as to feasibility of installing electric power for some of the machines but the exorbitant rates quoted by Edison Electric Ill. Co. of Boston prevented such action and after study by the Ray Engineering Co. of our power plant their recommendations were carried out boiler pressure increased by permission of the authorities and such changes made as to give us sufficient power for the present. This was done at an expenditure altogether of about $700.xx.”

Thomas Arthur Ray founded Ray Engineering Company in 1921. Ray served as an agent for valves and other products for steam plants and taught at Wentworth Institute in Boston, Mass. The company continues today in Westford, Mass., operated by Bill and Todd Ray, great-grandsons of the founder. We reached out to Bill and Todd with information about their company’s evaluation of the Schwambs’ boilers. In August 2025, they visited the Mill and examined the boilers in the cellar of the Dry House as well as the engineer’s logs (1937-1948), boiler inspection certificates, coal purchase records, and other items in the Mill’s archives.

Here are some of their observations:

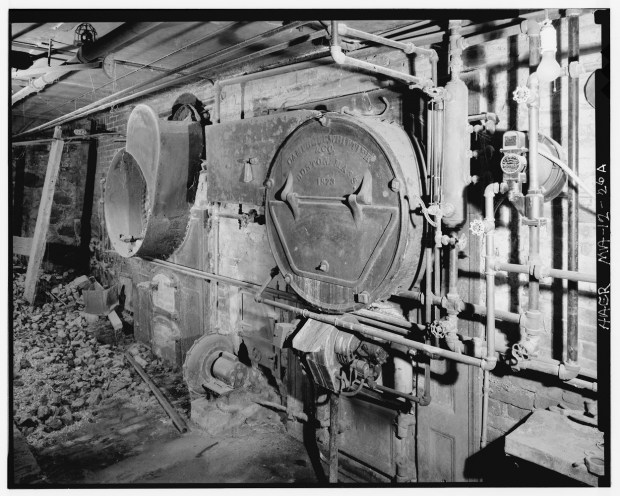

The two tube boilers were heated by coal and sawdust burning beneath. Fuel was not simply shoveled in; hot coal and ash were pushed beneath the boilers as far as 15 feet to the rear. The hot flue gas would flow beneath the boiler to the back where it would rise and return to the front of the boiler within the 24 metal tubes running through the water-filled boiler vessel. The water around these hot tubes would create steam which was sent to the engine in the Barn and to the radiators throughout the Mill. The flue gas would exit the tubes at the front of the boiler (with the heavy metal door in down position) and up through the chimney.

The brothers peered into the boilers with flashlights and were curious where the ash would have been raked out (there seems to be no door at the back of the building, although a smaller side door that may have provided access for cleaning).

Although the Dry House has two boilers, the Hartford Steam Boiler inspection certificates show only one boiler in use from 1910 onward. The certificates describe this boiler as rebuilt in 1908 by Roberts Iron Works, the same firm that the Schwambs later used for repairs. We assume this rebuilt boiler was the right boiler, which has all its tubes. The left boiler has no tubes, and the holes are plugged with scorched wooden stoppers, likely to prevent stray flue gas from blowing out, since the boilers were connected.

Confirming the account in the Clinton W. Schwamb Company annual meeting minutes, the 1924 boiler inspection certificate notes an increase in pressure from 100 to 150 psi. Bill Ray said that before giving the certificate Hartford Steam Boiler inspectors would have needed to see the Ray Engineering recommendation as well as any changes to gauges, valves or plugs required to operate at the new pressures.

Directly above the boiler is the room where the Schwambs dried countless boards from wood dealers in Boston and Charlestown. Inspecting that space, the Ray brothers agreed it would have been very hot indeed when the boiler was in use. The top of the boilers and the valve to connect or separate them in operation can be seen on that floor.

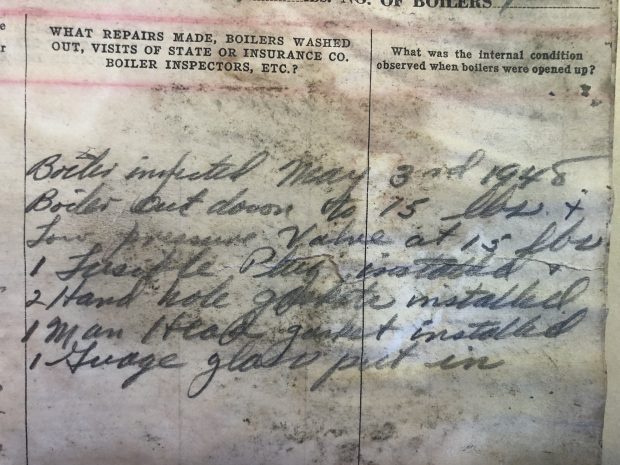

The engineering log ends with the Town of Arlington’s inspection of the boiler on May 3, 1948. The notes show that pressures were reduced to 15 psi, enough for heating only.

Before the brothers’ visit, we had interpreted these notes to mean that the town required a reduction in pressure out of concern for the safety of the 75-year-old boilers.

Bill Ray enlightened us. He thinks it more likely that the Schwambs intentionally converted the Mill to electric power in 1948. They would have installed electric motors to drive their machinery first. Then they would have modified the boiler for low pressure use only. This note in the log simply documents the changes made and the town’s inspection.

By law, a boiler rated for 150 psi required a licensed engineer to operate it. To eliminate the requirement for an engineer, the Schwambs modified the boiler to only operate at 15 psi, all the steam pressure they would need to heat the Mill. The change to electric power that the Schwambs avoided in 1924 could have made more sense to them in 1948, when electric rates may have come down, motor driven machines were more common, and engineers willing to feed, clean and maintain the 1875 boiler harder to hire and keep. The Schwambs had been through nine engineers in the previous 6 years.

The modifications listed on the last page of the engineer’s log make sense in this scenario, especially the change in the fail-safe “fusible plug” that would blow out in an overheated boiler at pressures higher than the specified 15 psi. The dated note records the changes that the town’s inspector would have confirmed before the Schwambs could legally discontinue employment of a licensed engineer.

This visit by Bill and Todd Ray is an example of research and expertise informing our knowledge of the Mill’s history. The steam plant – even more than the water wheel and turbine – was central to its operations, making year-round production possible from 1873 to 1948. We are so glad that, after 101 years, Ray Engineering could return to the Mill to shed light on the boiler’s operations.

Dermot Whittaker, Schwamb Mill Preservation Trust, Inc.

An Annual Appeal Reminder: All non-profits depend on the generosity of donors. The Old Schwamb Mill is no exception. Please consider making a donation to the Mill securely online here. Or send a check made out to Schwamb Mill Preservation Trust, Inc., to the Old Schwamb Mill, 17 Mill Lane, Arlington, MA 02476.

Steam co-existed with water turbine and waterwheel as power sources or more strictly sequenrial?

LikeLike

As we best understand it, this is the sequence:

1864 – 1872 Water wheel

1872 – ca 1888 Water wheel and steam engine (a small boiler used for 1872 only)

1888 – ca 1910 Water turbine and steam engine

ca. 1910 – 1948 steam engine

1948 – present electric motors

LikeLike