Fire has always been a danger to life and property, and nineteenth-century mill owners understood the risk it presented. This included woodworkers like the Schwamb brothers whose fortunes were tied to wooden buildings filled with dry lumber and machines that created sawdust, shavings, sparks, and the potential for ruin.

Warren A. Peirce wrote a historical sketch of the firefighting organizations of mid—nineteenth-century West Cambridge, now Arlington. His work was published in two parts, January 26 and February 2, 1894, in the Arlington Advocate. Peirce’s history informs our understanding of the Schwamb brothers’ early interest in fire fighting.

In the 1830s, residents of West Cambridge formed two independent fire companies: Enterprise Company based in the South fire district and Olive Branch Society based in the Northwest fire district. Both companies and the residents of their respective sections of town purchased their own hoses, equipment, and engines. The company known as the Olive Branch was organized on October 2, 1835. It included mill owners such as Ichabod Fessenden, William Schouler, and Stephen Locke, as well as John B. Perry who owned and operated the mill on the current site of the Old Schwamb Mill. By the 1850s, the Olive Branch Society included Charles Schwamb, then 26, as a member.

According to Peirce, in the 1850s these fire district companies were replaced by one controlled by the town, though largely including the same members. Charles Schwamb continued to serve in his company, which now included his brother Peter Schwamb and Theodore Diehl, another immigrant from Germany and a piano case maker. By 1863, the company included Theodore and Frederick Schwamb (brothers of Charles and Peter) and several others who would eventually be employees of Charles Schwamb at his picture frame manufactory: Charles S. Childs, George Kirsch, Gottlieb Stingle, and Jacob Bassing, as well as John E. Howard, a frame maker and probable employee. Other members of the company in 1863 — John Carroll, Arthur B. Moulton — worked in the piano manufacturing trade and were likely employees of Theodore Schwamb. When Highland Hose Company No. 2 was formed in 1872, Theodore Schwamb was still a member.

The building we know as the Old Schwamb Mill was bought and rebuilt by Henry Woodbridge in 1861 after a fire had destroyed the previous mill. A burned lintel can be seen over a bricked in window in the Mill’s brick foundation, which we believe is from the previous building. Brothers Charles and Frederick Schwamb bought the rebuilt mill from Woodbridge in 1864.

From 1861 to 1873, fire must have been present in or near the Mill. A photograph of the rebuilt Mill from around 1864 shows a chimney on the east side, and a photograph from 1869-1873 shows evidence of steam power onsite, which must have included a small coal fire within the building. Only in 1873 did the Schwambs install the coal boiler in an entirely separate building, with a full smoke stack — the building across Mill Lane that we today call the dryhouse.

Factory hours in most places, including Arlington, were longer in summer than in winter; longer days meant more light in the era before gas and electric lighting. Wayne Schwamb’s father Elmer, the last owner of the Mill, saved kerosene lamps that he says were used for late night work when necessary in those early days. This would have preceded Elmer’s working years, as the Mill installed electric power in 1917. Before 1917, the Mill’s journals show regular purchases of oils lamps, oil, chimneys, and kerosene in the darker months of the year. Lamps like these presented a risk of fire.

There is plenty of evidence that the Schwambs took the threat of fire seriously.

Red circles with nail hooks were painted on the walls throughout the Mill. We believe that these held “fire grenades,” glass containers containing a fire suppressant (often carbon tetrachloride, now considered a carcinogen). These grenades could be thrown at a fire where they would break and release the liquid contents, creating fire-suppressing fumes. Grenades like these were most common in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

By the twentieth century, it is clear the Schwambs were using conventional fire extinguishers. Some early twentieth-century extinguishers can still be found in the Mill, such as this Pyrene unit (empty of contents) mounted behind the band saw.

Inventories of the Mill from 1910 to 1913 include “6 fire pails.” The Schwambs also kept materials to recharge their foam extinguishers.

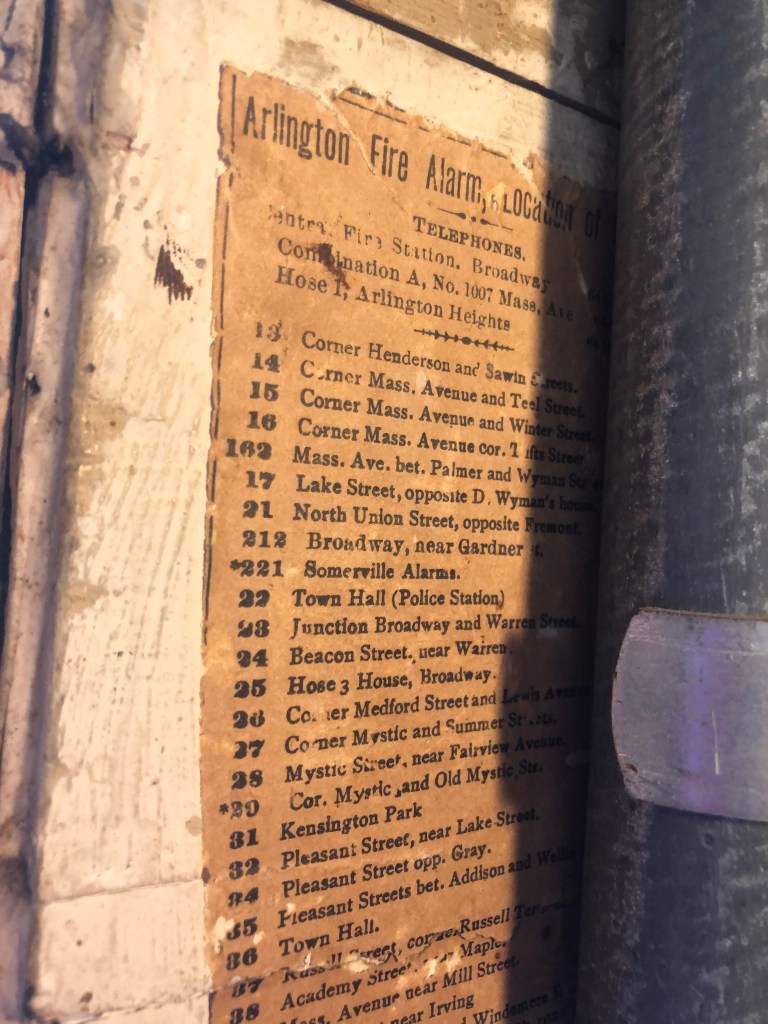

In Peirce’s historical sketch, he notes that “[i]n 1886, a telephone fire alarm system was adopted which was so marked an improvement over the old system that in 1889 the town adopted a complete fire alarm system which has already save its cost ten times over.”

By 1896, the Schwambs had a telephone in the old second floor office (now the Mill’s “frame gallery”). A list of the numbers for the Arlington fire stations, apparently cut from one of Arlington’s newspapers, is pasted to the wall.

By the early twentieth century, the Schwambs had installed a planing mill exhauster and ductwork to remove sawdust and wood shavings from the shop floor. The exhauster was made by the B.F. Sturtevant Company of Boston, in business making blowers, fans and exhausters since 1860. The system minimized saw dust in the air, potentially explosive, and piles of flammable saw dust beneath and around machines.

The system, still in use, creates a vacuum-like airflow that collects dust and shavings from the sanders and saws that create them. The dust is drawn from ducts leading from each machine to a larger duct in the basement. From here it is blown through a duct under Mill Lane to an underground chamber behind a brick wall adjacent to the boiler room in the dry house cellar. The fireman would shovel sawdust and shavings into the boiler, along with coal, to provide power and heat for the mill.

At this writing, we think that the exhaust system was in place as early as 1910, when records show expensive repairs were made to a blower or exhauster by B.F. Sturtevant Company. If installed before 1917, when electricity was first brought into the Mill, the exhauster would have been driven by the same steam power that drove the Mill’s other equipment. Readers interested in learning more about B.F. Sturtevant Company are encouraged to visit the website maintained by Vincent Tocco, Jr., who provided information on the Mill’s Sturtevant machines.

(right) Sturtevant planing exhauster still in use at the Mill. Payment for repairs to an exhauster suggest this machine was in use no later than 1910.

In 1927, the Schwambs installed a sprinkler system. In the words of the Clinton W. Schwamb Co. annual meeting minutes, this investment was

“…caused largely by a combination of circumstances beginning Feb. 4, 1927 when fire completely burned our boiler room and got into south side of lumber shed overhead. This happened about 1 A.M. and only a good piece of work by firemen saved us. We lost a few days’ output here and also in the adjustment for altho the fire insurance adjusters were fair we later found things not previously known. At the time we began to consider better fire protection and it was finally agreed between the owner of the property & the corporation that the present lease be abrogated, that rental be paid at rate of $250 to July 1, 1927 and at 300 thereafter a new lease for year being signed to this effect, the owner agreed to install a sprinkler system throughout plant which cut our insurance about 75% a vast savings. This went into effect Sept. 15th and should be reflected in future years expenses for insurance.”

As the board records make clear, the property and mill buildings were owned by Clinton Schwamb himself, as they had been by his mother Nellie Schwamb until her death, and monthly rent was paid for use of the buildings by the Clinton W. Schwamb Co. The increased rent paid by the company allowed Clinton to install the sprinkler system which protected his property and reduced the insurance rates paid by his company.

The sprinkler system is extensive, covering the cellar and all three floors of the mill. Sprinkler heads were installed throughout the building, including many hard-to-access spots: within the moulding storage racks, far back in the corners of the cellar, under the eves of the attic. One sprinkler is curiously placed within a cupboard in the second floor storage room, which in the Schwambs’ time was enclosed in chicken wire and had a locked door. Our interpretation is that this was a cabinet for chemicals and solvents, some of which may have been flammable.

The pipes throughout the building are normally dry, to prevent freezing during a heating failure. Only when a fire occurs and the sprinkler head is activated does the system begin pumping water from the cellar to the sprinkler head, ideally curtailing the fire until the firefighters arrive and thoroughly extinguish it. The Trust maintains this system today, alongside modern smoke detectors to warn of fire in real time.

The sprinkler system was put to a test on July 10, 1955. The Boston Globe reported:

“Arlington. Some 25 buildings were struck by lightning which also seared several utility poles and felled about 12 trees in East Arlington. No one was injured, police said.

The torrential rains flooded cellars and basements in the Arlington Heights, Morningside and East Arlington sections, police said.

A lightning bolt caused a $5000 fire in the 2 1/2-story woodworking plant of Clinton W. Schwamb Company on Mill lane. Fire Chief Thomas Egan said the bolt struck the roof and followed the wiring system to the main fuse box which exploded.”

As recorded in the minutes of the Clinton W. Schwamb Company’s annual meeting:

“… our factory was struck by lightning at about 4:30 PM at S.E. corner of shipping room which went across into top floor of main building setting a bad fire there and then going out an east window. We suffered quite a lot from water damage as six sprinkler heads went off & firemen had a hose line in on fire. Practically everything in shipping room ruined by fire or water & all goods finished or raw materials on first basement floor soaked & ruined except lumber which was recheck & loss was covered in all cases by insurance held by the Lumber Mutual Fire Co of Boston.”

Evidence of this fire remains throughout the southeast corner of the second floor. Charring is visible on the lower portions of the wall that were not replaced, the underside of the eleven-foot table used for sanding mouldings before shipping, and on the ceiling above. Charring is also visible directly above in the eves of the third floor. Staining consistent with the water damage remains on the older wooden walls.

Lumber Mutual Fire Company of Boston was the insurer used most often by the Clinton W. Schwamb Company. The earliest policy we have in the archives is from 1913 and details the parts of the business that were insured: machinery, tools, office equipment, supplies and product. As noted earlier, the buildings themselves were separately insured for their owner, Nellie Schwamb, mother of Clinton and Louis, and later Clinton himself.

Vigilance played a role in preventing fire. Over the years, the Arlington Advocate reported on arson at mills or fires set to piles of lumber in town. On holidays such as Hallowe’en and Independence Day, the Schwambs hired a watchman for the Mill at night. Wayne Schwamb, who worked at the Mill as a teenager in the 1950s and 1960s, recalls serving as a night watchman on such holidays.

On at least one occasion, Clinton Schwamb wrote the headquarters of a service provider to complain that its workmen persisted in smoking against Mill’s the policy. The prohibition on smoking remained in place under his son Elmer Schwamb. Wayne Schwamb recalls:

“Smoking was never allowed in the building during my time. Anyone who smoked had to do it outside. Smoking was a problem when customers would walk into the office smoking. My dad [Elmer] would explain that smoking was not permitted. The Mill did have signs posted ‘no smoking’.”

The “No Smoking” signs posted throughout the Mill were provided by the Lumber Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Boston, Mass. They appear on the first and second floors as well as in the cellar, where a bathroom break might occasion a smoke.

Today the Old Schwamb Mill does not allow candles or open flames of any kind. Modern smoke detectors warn of fire in real time. Extinguishers are present on every floor. Our goal is not simply to save a business, but to preserve a nineteenth-century factory and its way of life for generations to come.

Dermot Whittaker, Schwamb Mill Preservation Trust, Inc.

Excellent! THANK YOU!–Jan Forman Lucie, granddaughter of Edith Schwamb.

LikeLike

Thanks — and more Shares to come!

LikeLike

Great research, Derm – I’m delighted to read this!! Many many thanks! Peggy Clarke

>

LikeLike

THAT was fascinating! It is so cool that the very ordinary-looking OSM is a building of mystery, a veritable set of wooden jigsaw puzzle pieces with all these clues to its past. You look again, and there’s another piece of the story!

LikeLike